The Philippine government repeatedly declares its

commitment to the protection and promotion of human rights and to take

serious and concrete actions to address human rights issues as its

obligation under the 1987 Constitution and several international treaties.

But its false pretenses are fast wearing off with its dismal human rights

record since 2001, not to mention the unresolved cases prior to 2001. The

country has become a haven of torturers, murderers and abductors who are

comfortably enjoying impunity that breeds non-accountability.

Life for those who stand against the large-scale

corruption, unfair socio-economic policies and self- erving political

agenda of the powers-that-be is rocked by fear of arbitrary arrests,

enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions. The link between the

military and this specter of political violence has been undoubtedly

established by national and international institutions. But the Philippine

government, particularly its executive branch, has done nothing more than

sheer denial. In most cases, it stubbornly discredited any reports of

human rights violations without acting on these with due diligence. This

continues despite the sincere activism on the part of the judiciary in

coming up with legal remedies and mechanisms to purportedly address and

put an end to political violence.

However, after the Philippines underwent scrutiny on

its human rights performance under the Universal Periodic Review of the

United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC), it suddenly showed concern and

made itself open to dialogues with other stakeholders at various levels.

The Presidential Human Rights Committee (PHRC), an

inter-agency executive body organized to serve as the primary advisor to

the President in ensuring its compliance to the international human rights

obligations, is tasked to establish and forge a link and cooperation with

civil society in order to help the government draft a National Human

Rights Action Plan (NHRAP), a policy framework for institutional actions

on human rights and to put in place concrete and double measures. Its

efforts to finally work with non-government organizations by conducting

interactive dialogues and constructive discourses on human rights were

seen as a welcome development, though it should have been done long

before. It was eventually made possible on 17 March 2009 when the PHRC

together with the United Against Torture Coalition (UATC) and the Asian

Federation Against Involuntary Disappearance (AFAD) organized the first of

a series of public fora which intended to determine the advantages and

disadvantages of Philippine government’s plan to defer the implementation

of the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture’s (OPCAT).

The Philippine Government acceded to the Convention

Against Torture (CAT) and Other Cruel, Inhuman or DegradingTreatment and

Punishment on 18 June 1986. On 23 August 2007, President Gloria

Macapagal Arroyo signed the OPCAT’s instrument of ratification. This

instrument was subsequently transmitted to the Senate for concurrence. But

before the Philippine Senate concurs to the OPCAT, Malacanang has already

expressed its intention to defer the implementation of the OPCAT through

the announcement made by Executive Secretary Eduardo Ermita on 23

September 2008 during a multi-stakeholders’ workshop tackling the

establishment of the National Preventive Mechanism of the OPCAT at the

Traders Hotel in Pasay City. He indicated two reasons for considering to

opt out, to wit: to make necessary improvements of conditions in places of

detention and to harmonize the domestic laws for their full

implementation.

While

opting out is a prerogative of the state party provided under the Treaty’s

Article 24, this option however, elicited an adverse reaction from the

civil society particularly the members of the United Against Torture

Coalition (UATC), Philippines, a broad-based coalition of organizations

and individuals that has been working for years against torture in the

country. The UATC believes that this declaration is not only premature but

also it defeats no less than the very purpose of the OPCAT.

While

opting out is a prerogative of the state party provided under the Treaty’s

Article 24, this option however, elicited an adverse reaction from the

civil society particularly the members of the United Against Torture

Coalition (UATC), Philippines, a broad-based coalition of organizations

and individuals that has been working for years against torture in the

country. The UATC believes that this declaration is not only premature but

also it defeats no less than the very purpose of the OPCAT.

During the public forum, the members of the civil

society disproved the reasons of the government’s plan to defer. They

spelled out that OPCAT is designed as a practical tool to assist states in

its compliance with their existing obligations under the CAT. Its primary

purpose is to establish a system of regular and unannounced visits to

places of detention in order to prevent the commission of torture and

other forms of ill-treatment of persons deprived of their liberty and

conditions within detention facilities. They also brandished the

ambiguities of the government’s declaration of deferment that although the

OPCAT provides a state two options to defer, it can only choose one which

is either the establishment of the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) or

the opening of its doors to the visits of the Subcommittee and not to

both. They noted the government’s excuses that improving first the jail

conditions is not a prerequisite to the implementation of the OPCAT.

Moreover, harmonization of laws and policy adjustments to domestically

establish and implement it can be done within a year if the task is taken

seriously. They even assure the government that OPCAT works on the

principle of confidentiality, mutual trust and cooperation and does not

intend to berate or condemn the state. This opinion was also shared by no

less than Atty. Leila de Lima, Chairperson of the Commission on Human

Rights (CHR) who expressed the CHR’s strong support for the immediate

ratification and implementation of the OPCAT. She also mentioned the CHR’s

intention to play a preeminent role in the establishment and the working

of the NPM. According to her, the CHR under the present institutional

set-up, is acting as the national preventive mechanism and can work well

if their mandates are properly, effectively and aggressively utilized.

In

spite of CHR’s affirmation on the necessities and advantages of the OPCAT,

the representatives of the Philippine government who might have received

strict instructions from their bosses, were completely unmoved and did not

give any hint of rethinking their position. They offered a fool’s

consolation, though, by acceding to the suggestion that was put forward by

the civil society to form the Philippine OPCAT Working Group (POWG) whose

task is to formulate appropriate plans of action for the establishment of

the NPM through transparent, participative and consultative means. But how

POWG is placed in the government’s priority list, one can only surmise

because even before the body was instituted to do its work, the Philippine

government was already too eager to gloat itself in its second periodic

report as one of its major achievements at the CAT 42nd session from 27

April to 15 May 2009.

In

spite of CHR’s affirmation on the necessities and advantages of the OPCAT,

the representatives of the Philippine government who might have received

strict instructions from their bosses, were completely unmoved and did not

give any hint of rethinking their position. They offered a fool’s

consolation, though, by acceding to the suggestion that was put forward by

the civil society to form the Philippine OPCAT Working Group (POWG) whose

task is to formulate appropriate plans of action for the establishment of

the NPM through transparent, participative and consultative means. But how

POWG is placed in the government’s priority list, one can only surmise

because even before the body was instituted to do its work, the Philippine

government was already too eager to gloat itself in its second periodic

report as one of its major achievements at the CAT 42nd session from 27

April to 15 May 2009.

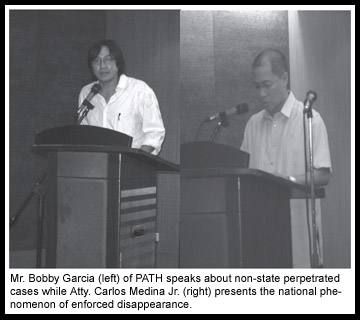

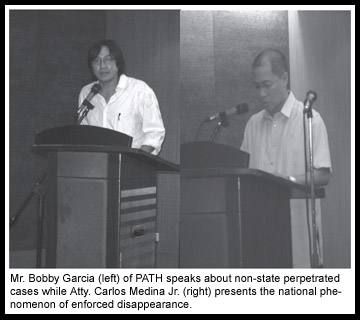

As the government savored this prized achievement, the

PHRC, which was overwhelmed with the “partnership” with civil society,

conducted a second forum on 22 May 2009 in the cooperation with the

Coalition Against Involuntary Disappearance (CAID) which enjoined all

stakeholders in a discussion about the on-going efforts of the Philippine

government to address the issue of enforced disappearances in the country.

However, the civil society looked at it as an opportunity to induce the

government into signing and ratifying the International Convention for the

Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance and to once and for

all, immediately enact the long awaited draft bill criminalizing enforced

or involuntary disappearances into a national legislation.

Apparently, the government was more convinced to take

the advice of the Department of National Defense that it cannot sign and

ratify the UN Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced

Disappearance as it may preempt its anti-insurgency campaign. It claimed

that even if the government is not a party to the treaty, it had already

taken a considerable number of specific measures to address this human

rights issues such as the creation of Task Force Usig and the Melo

Commission, and the institution of a better coordination between the

police and other agencies, strengthening of awareness of human rights

standards in different government line agencies and the establishment of

new human rights offices within the armed forces and the national police.

But

the civil society argued that these efforts were not enough as human

rights violations continue unabated. They attributed the difficult

prosecution of perpetrators to the absence of a standard definition that

not only confuses the public but also complicates the approaches and

interventions to be employed by different stakeholders to address the

issue. If only the government has done its homework, it would have found

this legal framework in the said UN treaty and the House Bill 5886, or the

consolidated disappearance bill authored by various lawmakers in the House

of Representatives which it finally approved on 5 March 2009 and

transmitted to the Senate. It is however unlikely that this piece of

legislation will be acted upon by the Upper House before the end of 14th

Philippine Congress as the 2010 elections are now fast approaching,

driving politicians frantic in assuring themselves of political survival.

But

the civil society argued that these efforts were not enough as human

rights violations continue unabated. They attributed the difficult

prosecution of perpetrators to the absence of a standard definition that

not only confuses the public but also complicates the approaches and

interventions to be employed by different stakeholders to address the

issue. If only the government has done its homework, it would have found

this legal framework in the said UN treaty and the House Bill 5886, or the

consolidated disappearance bill authored by various lawmakers in the House

of Representatives which it finally approved on 5 March 2009 and

transmitted to the Senate. It is however unlikely that this piece of

legislation will be acted upon by the Upper House before the end of 14th

Philippine Congress as the 2010 elections are now fast approaching,

driving politicians frantic in assuring themselves of political survival.

In a desperate bid to make up for its inaction, the

PHRC drew the first straw in suggesting that it planned to replicate the

creation of a Working Group on enforced disappearance patterned to that of

the Philippine OPCAT Working Group (POWG). But before this body could be

created, the PHRC made a major blunder of issuing a malicious and

erroneous statement released and circulated by the Philippine Embassy in

Washington DC utterly discrediting the report of Karapatan on the

alleged disappearance of a Fil-Am activist, Melissa Roxas et al and

erroneously quoting the Asian Federation Against Involuntary

Disappearances (AFAD) and the Families of Victims of Involuntary

Disappearance (FIND) which, accordingly, made an initial investigation

discrediting the case.

By dragging the name of the CAID, FIND and the AFAD and

illustrating them as “more credible” groups to deal with, the PHRC has,

early enough, exposed its ill-intent of not only denying cases of human

rights violations but also of sowing divisions among civil society

organizations and pitting them against each other just to cover-up its

ineptness in solving these. The government gains nothing from this obvious

political vilification except to earn the contempt of the civil society in

the face of incontrovertible facts pointing to its lip-service approach in

addressing the problem. A virulent statement such as this especially

coming from the human rights office of the President manifests a wishful

thinking of a possible qualitative and quantitative improvement in the

human rights situation in the country during the remaining year of the

Arroyo administration in the absence of the latter’s sincerity and

political will to do so.

Dim, indeed, is the future of human rights in this

country.

While

opting out is a prerogative of the state party provided under the Treaty’s

Article 24, this option however, elicited an adverse reaction from the

civil society particularly the members of the United Against Torture

Coalition (UATC), Philippines, a broad-based coalition of organizations

and individuals that has been working for years against torture in the

country. The UATC believes that this declaration is not only premature but

also it defeats no less than the very purpose of the OPCAT.

While

opting out is a prerogative of the state party provided under the Treaty’s

Article 24, this option however, elicited an adverse reaction from the

civil society particularly the members of the United Against Torture

Coalition (UATC), Philippines, a broad-based coalition of organizations

and individuals that has been working for years against torture in the

country. The UATC believes that this declaration is not only premature but

also it defeats no less than the very purpose of the OPCAT. In

spite of CHR’s affirmation on the necessities and advantages of the OPCAT,

the representatives of the Philippine government who might have received

strict instructions from their bosses, were completely unmoved and did not

give any hint of rethinking their position. They offered a fool’s

consolation, though, by acceding to the suggestion that was put forward by

the civil society to form the Philippine OPCAT Working Group (POWG) whose

task is to formulate appropriate plans of action for the establishment of

the NPM through transparent, participative and consultative means. But how

POWG is placed in the government’s priority list, one can only surmise

because even before the body was instituted to do its work, the Philippine

government was already too eager to gloat itself in its second periodic

report as one of its major achievements at the CAT 42nd session from 27

April to 15 May 2009.

In

spite of CHR’s affirmation on the necessities and advantages of the OPCAT,

the representatives of the Philippine government who might have received

strict instructions from their bosses, were completely unmoved and did not

give any hint of rethinking their position. They offered a fool’s

consolation, though, by acceding to the suggestion that was put forward by

the civil society to form the Philippine OPCAT Working Group (POWG) whose

task is to formulate appropriate plans of action for the establishment of

the NPM through transparent, participative and consultative means. But how

POWG is placed in the government’s priority list, one can only surmise

because even before the body was instituted to do its work, the Philippine

government was already too eager to gloat itself in its second periodic

report as one of its major achievements at the CAT 42nd session from 27

April to 15 May 2009. But

the civil society argued that these efforts were not enough as human

rights violations continue unabated. They attributed the difficult

prosecution of perpetrators to the absence of a standard definition that

not only confuses the public but also complicates the approaches and

interventions to be employed by different stakeholders to address the

issue. If only the government has done its homework, it would have found

this legal framework in the said UN treaty and the House Bill 5886, or the

consolidated disappearance bill authored by various lawmakers in the House

of Representatives which it finally approved on 5 March 2009 and

transmitted to the Senate. It is however unlikely that this piece of

legislation will be acted upon by the Upper House before the end of 14th

Philippine Congress as the 2010 elections are now fast approaching,

driving politicians frantic in assuring themselves of political survival.

But

the civil society argued that these efforts were not enough as human

rights violations continue unabated. They attributed the difficult

prosecution of perpetrators to the absence of a standard definition that

not only confuses the public but also complicates the approaches and

interventions to be employed by different stakeholders to address the

issue. If only the government has done its homework, it would have found

this legal framework in the said UN treaty and the House Bill 5886, or the

consolidated disappearance bill authored by various lawmakers in the House

of Representatives which it finally approved on 5 March 2009 and

transmitted to the Senate. It is however unlikely that this piece of

legislation will be acted upon by the Upper House before the end of 14th

Philippine Congress as the 2010 elections are now fast approaching,

driving politicians frantic in assuring themselves of political survival.