"Lose no hope . Keep fighting.

Guard the memories .

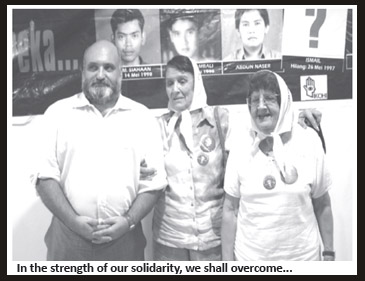

We wear heascarves with the names of our

disappeared children.

We also bring the pictures of our children.

These prevent us from forgetting them.

We need to show that the disappeared are human

beings; they have names, faces and families."

Taty Almeida’s message to the Indonesian human rights movement, 25 April

2009

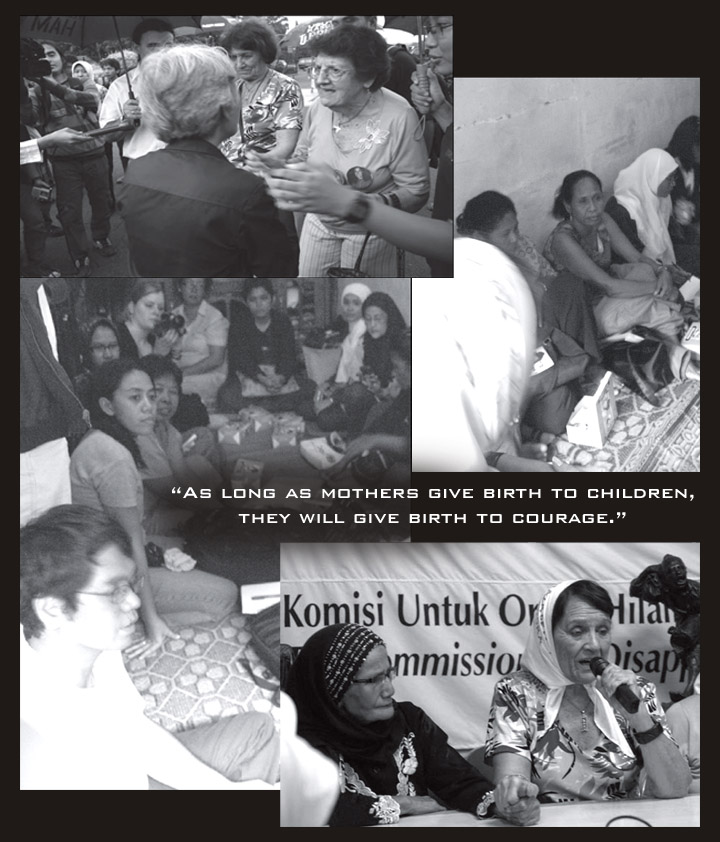

In April 2009, the Indonesian human rights community received a visit by

two special guests from Argentina. The special guests were neither the

famous football players like Diego Maradona and Lionel Messi. Nor were

they the popular first couple, President Cristina Fernandez Kirchner and

her husband, former Argentinian president Néstor Kirchner. The two special

guests were Señora Lydia

Taty Almeida and

Señora Aurora Morea of the

internationally known Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Linea Fundadora. They

came to Indonesia in order to commemorate the Indonesian Women’s Day

(known as Kartini Day) and the 11th anniversary of the Commission for the

Disappearances and Victims of Violence (KontraS).

Taty Almeida and

Señora Aurora Morea of the

internationally known Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Linea Fundadora. They

came to Indonesia in order to commemorate the Indonesian Women’s Day

(known as Kartini Day) and the 11th anniversary of the Commission for the

Disappearances and Victims of Violence (KontraS).

From their physical appearance, they look like two 80

year old ordinary grandmothers. But from their stare and body language, we

can see that they are women of strong character and whose years of pain

and struggle have developed in them an inner confidence in their capacity

to struggle for a world without desaparecidos. Their senior years have

never ever diminished their persistence and courage in their struggle for

life – for truth, justice, redress and the reconstruction of the

historical memory of their beloved desaparecidos.

Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo Was Initiated by 14

Mothers….

Taty and Aurora are leading members of the well-known Las Madres de Plaza

de Mayo –Linea Fundadora. If translated to English, it means “The Mothers

of the May Square – the Founding Line.” It is an organization of mothers

whose sons and/or daughters were made to disappear when Argentina was

under the military junta from 1976 until 1983.

The establishment of the organization was started by those mothers who

searched for their disappeared children from the police office, the

military, ministerial offices, and even the churches. It was in these

places that they met each other. On one occasion, one of the mothers,

Azucena Villaflor de Devicenti, said to the others,

“If we do this alone, we will not get anything. Why

don’t we go to the Plaza de Mayo, and when we organize as a group, Jorge Videla will certainly want to meet us .... “

On Thursday afternoon, 30 April 1977, 14 women gathered

at the heart of Buenos Aires, in the Plaza de Mayo in front of the

Casa

Rosada.1 They were dressed in black with white scarves around their heads,

wherein the names of their disappeared sons and daughters are imprinted

and carried signs emblazoned with photographs of those whose whereabouts

are unknown.

In Argentina’s Christian culture, women are highly

valued and respected. Yet, despite their being women, their action was not

safe. The military junta was apparently angry with the mothers. It did not

only insult them by calling them the mad mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Las Locas de

Plaza de Mayo), but also threatened and terrorized them. Several

times, they had to be dragged to the truck of the army and arrested a few

days in the police office.

Furthermore, some of its leaders were also arrested,

tortured and made to disappear. One of them was its founder, Azucena

Villaflor de Devicenti who was made to disappear on 10 December 1979. In

July 2005, the body of Villaflor, together with those of two other

mothers, was identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Equipo

Argentino de Antropologia Forense or EAAF). The bodies showed fractures

consistent with a fall and impact against a solid surface, which confirmed

the hypothesis that the prisoners had been taken in one of the many “death

flights” (vuelos de la muerte) recounted by former naval officer, Adolfo

Schilingo. In these flights, prisoners were drugged, stripped naked and

flung out of the aircraft flying over the Atlantic ocean.

Furthermore, some of its leaders were also arrested,

tortured and made to disappear. One of them was its founder, Azucena

Villaflor de Devicenti who was made to disappear on 10 December 1979. In

July 2005, the body of Villaflor, together with those of two other

mothers, was identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Equipo

Argentino de Antropologia Forense or EAAF). The bodies showed fractures

consistent with a fall and impact against a solid surface, which confirmed

the hypothesis that the prisoners had been taken in one of the many “death

flights” (vuelos de la muerte) recounted by former naval officer, Adolfo

Schilingo. In these flights, prisoners were drugged, stripped naked and

flung out of the aircraft flying over the Atlantic ocean.

Of the two mothers visiting Indonesia, Taty Almeida

joined Las Madres because her son, Martin Alejandro Almeida was taken by

military intelligence officers on 17 June 1975. When he disappeared,

Alejandro was 20 years and a medical student. Until this day, Taty does

not have any information about the fate and whereabouts of her beloved

son.

Aurora Morea joined Las Madres because her daughter and

son-in-law, Susana Perdini de Bronzal and her husband, disappeared and

later killed. Susana was 27 years old, an architect who was active in

political activities against the military junta. In an investigation and

exhumation of the EAAF on this case, Susana’s remains were found and

identified in 1999.2

A Success Story…

The long and difficult struggle of the mothers in Argentina and abroad

since 1977 has resulted in the development of the international human

rights mechanisms. In the late 1970s, issues of enforced disappearances

came to the attention of the United Nations, which ushered in the

establishment of the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or

Involuntary Disappearances (UNWGEID) in 1980. More than a decade later, on

18 December 1992, the United Nations unanimously adopted the Declaration

for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced or Involuntary

Disappearances.

Furthermore, the struggle of Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, along with other

victims’ organizations including the constituents of the Asian Federation

Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) and other international human

rights organizations also have successfully convinced the United Nations

to finally adopt a legally binding normative instrument, which is the

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced

Disappearance (herein after referred to as The Convention) in December

2006. In fact, Argentina is the second out of the 11 states, so far, to

ratify the treaty. The Argentinean government has made clear its support

to the establishment of an independent committee to monitor the treaty’s

implementation. Other countries that ratified the Convention are Albania,

Bolivia, Cuba, France, Honduras, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Senegal, Uruguay and

Mali.

Because of the struggle of the Mothers of the May Square, the new

president of post-military junta in Argentina, Raúl Alfonsín established

the National Commission for Missing Persons (CONADEP). After working or

one year, the CONADEP had successfully disclosed the practices of

disappearances by the military junta within the period of 1976 - 1983 and

issued a well-known report, entitled Nunca Mas (Never Again) which, as

American Legal Philosopher Ronald Dworkin pointed out, it is “a report

from hell.”

The Nunca Mas has successfully revealed the pattern of disappearances,

places of clandestine detention, methods of torture and the identity of

the victims and the perpetrators. In the working period of only a year,

CONADEP was able to identify 8,000 victims, from the 30,000 persons whom

they believe to have forcibly disappeared. The Nunca Mas was then used as

one of the references to try members of the military junta responsible for

the disappearances. The scheme of reparations for the victim was also

undertaken in Argentina with reference to CONADEP report.

Las Madres of Indonesia; Women Human Rights Defenders

Like Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, there are also many mothers of the

disappeared in Indonesia. Gross human rights violations occurred in 1997 –

1999, particularly during the disappearances of pro-democracy activists,

the May Riots and the shooting of students known as Trisakti, Semanggi I

and Semanggi II (TSS). Since then, the Indonesian mothers of the

disappeared began to struggle for justice and human rights in Jakarta, not

to mention those mothers in other parts of the country, such as Aceh and

Papua, who are also struggling for the same cause.

Starting at the end of March 1998, some parents began

to worry because of the news that their children were abducted by the

military. Among them were the parents of Faisol Riza; Raharja Waluya Jati;

Mugiyanto (the author); Nezar Patria; Suyat Petrus Bima; Anugerah; Andi

Arief; Herman Hendrawan and the wife of Wiji Thukul. The parents of Yani

Afri, Noval Alkatiri, Yadin Muhidin and Ucok Siahaan followed. They all

reported their missing loved ones to the Commission for Missing Persons

and Victims of Violence (KontraS), chaired by the late Munir.

They began to search for their disappeared loved ones

by visiting the Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM), military

headquarters, police headquarters, military police headquarters, House of

Parliament, the Attorney General and different ministries of government in

order to relay one common question: “ Where are our children? ” Until now,

the question remains unanswered.

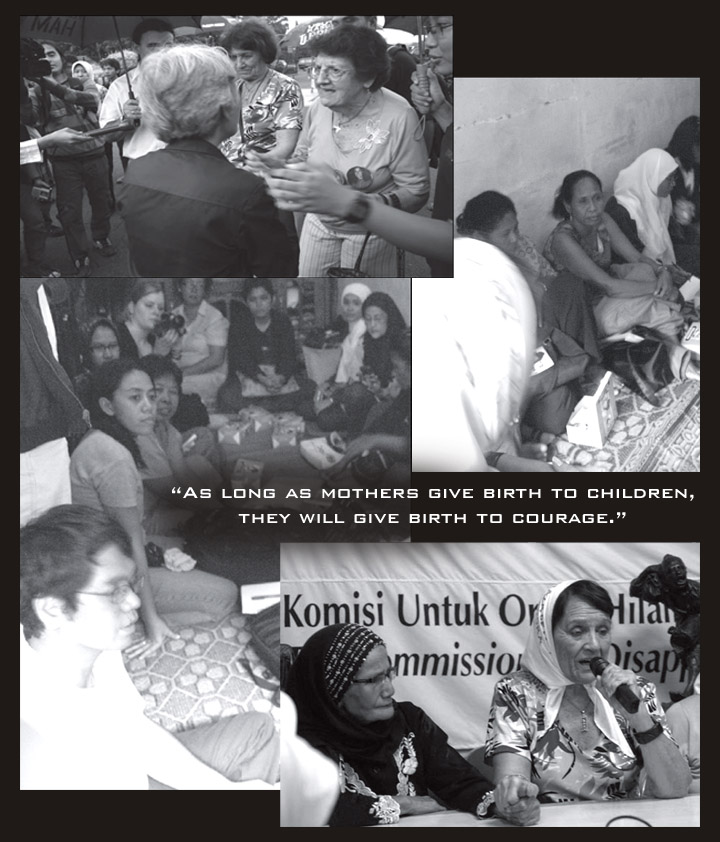

In the process of their search and continuing struggle,

the mothers are the most persistent and brave. There were times in 1999

when in front of the House of Parliament and the Ministry of Defense, the

mothers were those who defied the military which were completely armed and

did all what they could to force them to leave. As musician, Margaret

Wakeley mentioned about these mothers, “As long as mothers give birth to

children, they will give birth to courage.”

A Message to the Struggling Indonesian Mothers

While in Indonesia, Taty and Aurora always delivered

inspiring messages to their fellow mothers whose children have also

disappeared. “Keep fighting, never surrender, never forget!”

In an exclusive interview with leading Indonesian

English newspaper, the Jakarta Post, Taty said, “Lose no hope. Keep

fighting. Guard the memories. We wear headscarves with the names of our

disappeared children. We also bring the pictures of our children. In so

doing, we will never forget them all the more. We need to show that the

disappeared are human beings; they have names, faces and families.”

Like the goals of the madres in Argentina, the ultimate

goals of victims’ families’ struggle in Indonesia go beyond their own

personal interests. Transcending personal gratification, these goals are

indefatigably being fought for the sake of the country’s future so that

never again will enforced disappearances happen to anyone. “Let us be the

last victims,” Misiati Utomo, a mother of a disappeared, emphatically

said.

The appeal of “never forget” becomes very important and

relevant in the context of Indonesia’s upcoming presidential elections.

Some investigations by official state institutions, such as Komnas HAM,

found out command responsibility involvement of the retired General Wiranto and retired Lieutenant General Prabowo Subianto in the cases of

enforced disappearances and other human rights violations. Both military

men are vice presidential candidates for the 8 July 2009 elections.

Especially for the victims’ families and the human rights community in

Indonesia, the candidacy of these persons is a threat to human rights.

They should never be holding public office and instead, be held

accountable for the atrocities they have committed.

For whatever reasons - ethical, moral, political,

cultural or social - justice and accountability are imperative. Founded on

this principle, one member of Las Madres said, “human errors can be

pardoned; what is beyond the frontiers of humanity cannot.”

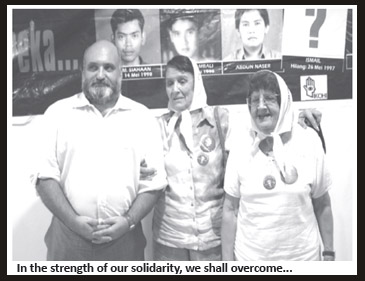

The visit of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo has

inspired and encouraged human rights activists in Indonesia, particularly

the women human rights defenders. Their visit was a real expression of

genuine solidarity among victims of repression under military regime. As

aspired for by one Indonesian mother, “it Mugiyanto is the present

Chairperson of the AFAD. He is the founding Chairperson of IKOHI. He

himself has been a victim of enforced disappearance when he was kept in

secret detention, during which he was physically and psychologically

tortured by the Kopassus immediately after the fall of Suharto in 1998.

Three months later, he was released. would be very ideal to strengthen

such sincere international solidarity, extending it to other continents

that are experiencing similar sufferings and having the same dream for

justice.”

_____________________________

End notes:

1 La Casa Rosada, (Spanish for “The Pink House”), officially known as the

Casa de Gobierno (“Government House”) or Palacio Presidencial (“The

Presidential Palace”), is the official seat of the executive branch of the

Government of Argentina. Source: Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

2 Annual Report 2000 of the Equipo Argentino de Antropologia Forense.

Mugiyanto is the present Chairperson of the AFAD. He is the

founding Chairperson of IKOHI. He himself has been a victim of enforced

disappearance when he was kept in secret detention, during which he was

physically and psychologically tortured by the Kopassus immediately after

the fall of Suharto in 1998. Three months later, he was released.

Taty Almeida and

Señora Aurora Morea of the

internationally known Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Linea Fundadora. They

came to Indonesia in order to commemorate the Indonesian Women’s Day

(known as Kartini Day) and the 11th anniversary of the Commission for the

Disappearances and Victims of Violence (KontraS).

Taty Almeida and

Señora Aurora Morea of the

internationally known Las Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Linea Fundadora. They

came to Indonesia in order to commemorate the Indonesian Women’s Day

(known as Kartini Day) and the 11th anniversary of the Commission for the

Disappearances and Victims of Violence (KontraS). Furthermore, some of its leaders were also arrested,

tortured and made to disappear. One of them was its founder, Azucena

Villaflor de Devicenti who was made to disappear on 10 December 1979. In

July 2005, the body of Villaflor, together with those of two other

mothers, was identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Equipo

Argentino de Antropologia Forense or EAAF). The bodies showed fractures

consistent with a fall and impact against a solid surface, which confirmed

the hypothesis that the prisoners had been taken in one of the many “death

flights” (vuelos de la muerte) recounted by former naval officer, Adolfo

Schilingo. In these flights, prisoners were drugged, stripped naked and

flung out of the aircraft flying over the Atlantic ocean.

Furthermore, some of its leaders were also arrested,

tortured and made to disappear. One of them was its founder, Azucena

Villaflor de Devicenti who was made to disappear on 10 December 1979. In

July 2005, the body of Villaflor, together with those of two other

mothers, was identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Equipo

Argentino de Antropologia Forense or EAAF). The bodies showed fractures

consistent with a fall and impact against a solid surface, which confirmed

the hypothesis that the prisoners had been taken in one of the many “death

flights” (vuelos de la muerte) recounted by former naval officer, Adolfo

Schilingo. In these flights, prisoners were drugged, stripped naked and

flung out of the aircraft flying over the Atlantic ocean.