A Dream-Come-True

“In 2000, Macarena discovered the truth of who she

thought her parents were. They were not her real parents. She was adopted.

Her real parents were two young Argentineans who were tortured and made to

disappear. Her father was murdered. Her mother disappeared.

Her mother, Maria Claudia was eight months pregnant

when she was forcibly taken by the armed forces of the Argentinean

dictatorship and, in an act of coordination between the military of both

countries, was illegally transferred to Uruguay. She was detained in a

secret detention cell until she gave birth. Her perpetrators’ sole

objective was to give her baby as a gift of courtesy to a high-ranking

Uruguayan military man. Macarena lived with her mother during her first

months in an underground detention center together with other detainees,

many of whom had also disappeared. Her first months in life were

characterized by darkness, torture and death until she was given for

adoption to the police officer. Thirty years after, she is still

searching. The military men have given false information and pointing at

different places as possible burial sites of her mother. Each exhumation…

each false information has deepened her suffering.

Macarena never knew her parents. Her grandmother died

searching for her and without ever being able to know her

granddaughter whom she loved very much even if she never had the

possibility to carry her in her arms.

Represented in her story is the history of several

children who disappeared in Latin America, majority of whose identities

have never been traced. They continue to live and consider as parents

those who tortured and killed their real parents.1”

This and many other poignant stories of the

desaparecidos in Latin America, (which signify individual and

collective pain of a continent devastated by years of dictatorship), are

the very stories that urged families of the disappeared to dream YOU By

Mary Aileen Diez-Bacalso for the establishment of an international treaty

protecting people from enforced disappearances.

In Latin America, families of the disappeared dared to

dream… they dared to struggle for the realization of their dream. This

dream, coupled with persistent struggle for truth, justice, reparation and

memory and persistent knocking at doors of national and international

authorities has now come to be realized… What is now the UN Convention for

the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, adopted without

a vote by the UN General Assembly on 20 December 2006, is a dream-come

true three decades later. It is presently signed by 81 states and ratified

by 11, namely, Albania, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Honduras, France,

Senegal, Kazakhstan, Cuba, Uruguay, and Mali. Germany and Spain will

deposit their instruments of ratification soon.

Not a single ratification has come from Asia.

The Heart of the International Treaty

What is it in the Convention that makes it one of the

strongest international human rights treaties, thus, making it an

imperative for governments to sign, ratify and implement its provisions?

The Convention establishes the autonomous human right

of every person not to be subjected to enforced disappearance. This right

is recognized by everyone, everywhere and States cannot invoke any

exceptional circumstance to justify enforced disappearance. As Atty.

Gabriela Citroni, member of the Italian delegation of the then drafting

and negotiation body aptly put in her speech in an AFAD-FEDEFAM

event at the UN in Geneva held in March 2009:

“...this new right represents a historical achievement,

because before the adoption of the Convention, such right had never

been recognized and it was necessary to invoke a

number of other human rights which are impaired by the offense.”

The

Convention also recognizes the right to know the truth about the

circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of

the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person. As Atty. Citroni

further said, providing for this right is the first instance that has

occurred in international human rights law.

The

Convention also recognizes the right to know the truth about the

circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of

the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person. As Atty. Citroni

further said, providing for this right is the first instance that has

occurred in international human rights law.

Since desaparecidos are held in secret

detention, the Convention guarantees that no one shall be held in secret

detention. States must hold detained people only in officially recognized

places.

The Convention also adopts a broad definition of

victims: not only the person who disappeared, but also any individual who

has suffered harm as the direct result of an enforced disappearance. The

Convention recognizes several rights of the victims of enforced

disappearances:

•The right to report to the authorities a case of

enforced disappearance and have it promptly, thoroughly and impartially

investigated;

• The right to obtain reparation (including rehabilitation, restitution,

satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition, such as public ceremonies

of apology, the provision of medical and psychological treatment, etc.)

and prompt, fair, adequate compensation (covering material and moral

damages);

• The right to form and participate freely in organizations concerned with

the search for disappeared people and the assistance of victims and their

relatives;

• The Convention provides that States must prevent and punish under their

criminal law the wrongful removal of:

- children who are subjected to enforced disappearance;

- children whose parents are subjected to enforced disappearance;

- children born during the captivity of a mother subjected to enforced

disappearance.

• States must prevent and sanction the falsification,

concealment or destruction of documents attesting the true identity of the

mentioned children;

• States must have legal procedures to review and, if appropriate, to

annul the adoption or placement of children that originated in an enforced

disappearance.

A Committee on Enforced Disappearances composed of 10

experts and entrusted with the mandate to monitor the treaty’s

implementation by States Parties and with multiple functions, shall be

established.

And Disappearances Continue…

That

the Convention enters into force without delay and that it be implemented

universally are moral obligations of states. In all nooks and corners of

the world, enforced disappearances continue to steal precious lives. The

United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances

(UNWGEID) reported during the 10th session of the UN Human Rights Council

in March 2009 that: “The total number of cases transmitted by the Working

Group to Governments since its inception is 52,952. The number of cases

under active consideration that have not yet been clarified, closed and

discontinued stands at 42,393 and concerns 79 States….” Of the 79 states,

21 are Asian.

That

the Convention enters into force without delay and that it be implemented

universally are moral obligations of states. In all nooks and corners of

the world, enforced disappearances continue to steal precious lives. The

United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances

(UNWGEID) reported during the 10th session of the UN Human Rights Council

in March 2009 that: “The total number of cases transmitted by the Working

Group to Governments since its inception is 52,952. The number of cases

under active consideration that have not yet been clarified, closed and

discontinued stands at 42,393 and concerns 79 States….” Of the 79 states,

21 are Asian.

To cite a couple of places in Asia, in Jammu and

Kashmir, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) has

documented 8,000 cases since the early ‘90s. This number has multiplied

into thousands of suffering family members, mostly women and children

whose lives have been destroyed by the loss of their loved ones, most of

whom were family breadwinners. One of the initial proofs of disappearances

are the 940 skeletal remains found in the borders of Kashmir and Pakistan

in 2008 and due to fear of reprisals by the Indian government, they could

not be unearthed and identified and literally, they remain as skeletons in

the closet. Worse still, human rights defenders in the area are harassed.

One example is the case of APDP patron Parvez Imroz whose house was bombed

by 9 to 10 men believed to be members of the Central Reserved Force (CRF)

and Special Operations Group (SOG) because of his expose’ about the

skeletal remains.

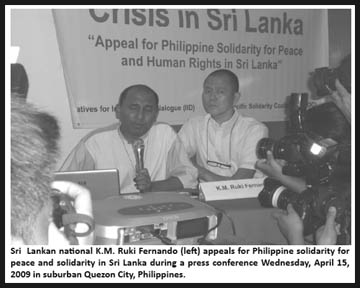

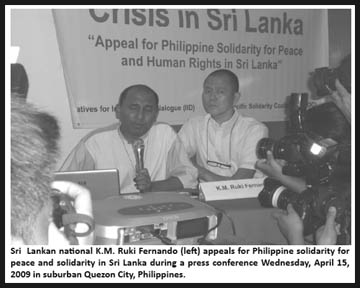

In a visit of Mr. Ruki Fernando to the Philippines in

May 2009, he sought the solidarity of the Filipinos with the Sri Lankan

people who excruciatingly suffer the pain of gross human rights

violations. His presentation centered on the war between the Liberation

Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the government; the war against

civilians; the war against dissenters resulting in a bloodbath. As he

vividly demonstrated gory pictures of deaths, he also presented the

worsening phenomenon of disappearances, not to mention the unresolved

cases from the ‘90s. When he was presenting his powerpoint, entitled, “Sri

Lanka: Island of Blood, Fear and Tears,” one could imagine how fearful

life would be for him back to his own country, since he is one of the Sri

Lankan human rights defenders whose lives are at great risk.

Looking

back to the AFAD’s visit to this so-called “Pearl of the Indian Ocean” and

“Paradise Island,” this writer recalls the families of the disappeared

whose loved ones disappeared in the nineties and endlessly clamored for

truth about their disappearance. They told stories of their kin who never

saw light at the end of the tunnel and ended up committing suicide.

Looking

back to the AFAD’s visit to this so-called “Pearl of the Indian Ocean” and

“Paradise Island,” this writer recalls the families of the disappeared

whose loved ones disappeared in the nineties and endlessly clamored for

truth about their disappearance. They told stories of their kin who never

saw light at the end of the tunnel and ended up committing suicide.

“The modus operandi of the widespread abductions and disappearances

we witness in Sri Lanka today is similar to what we saw in the late ‘80s

and early ‘90s. President Rajapakse, who, as a Member of Parliament then,

was in the forefront of the struggle against these incidents. Now, his

regime has become one of the world’s worst perpetrators of enforced

disappearances. Members of the security forces, police and pro-government

groups are alleged to be involved in these incidents.” Thus, stated Mr.

M.C.M. Iqbal, former member of the National Commission on Human Rights in

a meeting with the members of the UNWGEID held in Geneva, Switzerland in

March 2009. Like Mr. Fernando, Mr. Iqbal’s life is in peril.

Many

similar stories of woes originate in Afghanistan, Burma, China, East

Timor, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and several other

Asian countries. These make us wonder why is it that in this supposedly

civilized world and despite the membership of a number of these countries

in the prestigious UN Human Rights Council, disappearances and many other

forms of human rights violations continue to be the order of the day. They

speak of lives lost, hearts broken, families, communities and the greater

society devastated by this crime against humanity.

Many

similar stories of woes originate in Afghanistan, Burma, China, East

Timor, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and several other

Asian countries. These make us wonder why is it that in this supposedly

civilized world and despite the membership of a number of these countries

in the prestigious UN Human Rights Council, disappearances and many other

forms of human rights violations continue to be the order of the day. They

speak of lives lost, hearts broken, families, communities and the greater

society devastated by this crime against humanity.

That there is no single ratification from Asia is a

cause for alarm in a continent that submitted a large number of cases to

the UNWGEID.

Uphill Struggle for Signatures and Ratification in Asia

The

Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) has made

numerous efforts to convince governments of Thailand, Indonesia, the

Philippines, Sri Lanka and Nepal to ratify the Convention. Concrete

efforts were accomplished through the series of fora on the Convention,

meetings with government agencies, distribution of campaign materials,

etc. At the international level, letters calling on governments worldwide

to ratify the Convention have been sent.

The

Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) has made

numerous efforts to convince governments of Thailand, Indonesia, the

Philippines, Sri Lanka and Nepal to ratify the Convention. Concrete

efforts were accomplished through the series of fora on the Convention,

meetings with government agencies, distribution of campaign materials,

etc. At the international level, letters calling on governments worldwide

to ratify the Convention have been sent.

In the Philippines, for instance, the AFAD Secretariat

has facilitated several fora on the Convention since the signing ceremony

in Paris in February 2007. One of the latest was held on 22 May 2009,

realized through the joint efforts of AFAD, the Coalition Against

Involuntary Disappearances (CAID) and the Presidential Human Rights

Committee (PHRC) and participated in by a good number of government

agencies. The latest forum was conducted on 4 June during the AFAD’s 11th

anniversary. Yet, government agencies, while insistently assuring civil

society of their resolve to stop disappearances, said that the 15- year

old national bill criminalizing enforced disappearances be enacted into

law first before the Convention could be ratified. But until when shall we

wait when, in addition to almost two thousand cases already documented by

the Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance (FIND), more than 200

cases have already been documented by Karapatan since 2001.

Fourteen years have passed since this bill was first filed by the late

House of Representatives Member, Bonifacio Gillego, but it has not yet

seen the light of day.

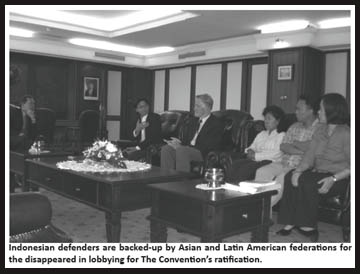

In Indonesia, the two member-organizations of the AFAD

and the Latin American Federation of Associations of Relatives of

Disappeared -Detainees (FEDEFAM) had, on several occasions, lobbied

for the treaty. More recently, in March this year, two representatives

from the Madres de Plaza de Mayo – Linea Fundadora came to

Indonesia to help in pressing the Indonesian government to ratify.

Earlier, Mr. Patricio Rice, FEDEFAM Adviser and this writer,

representing the AFAD, together with KontraS and IKOHI

visited government agencies such as the National Commission on Human

Rights, the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and

spoke before civil society regarding the importance of the Convention. The

promise of the Indonesian government sometime in 2007 at a High Level

segment session of the UN Human Rights Council to sign the international

treaty remains unfulfilled. Now that President Sucilo Bambang Yudhoyono

has received a second term, such promise has, once and for all, to be

finally fulfilled simultaneous with the resolution of the murder of Munir.

In the March 2009 discussion on Agenda Item 3, i.e.

Civil and Political Rights of the UN Human Rights Council, listening to

the interventions of the Asian states after the Chair of the UNWGEID

presented his 2008 report, this writer reckons that only the Thai

government stated serious consideration of becoming a party to the treaty.

This was reiterated in the parallel event which the AFAD and the

FEDEFAM organized on the same occasion. Marred by political

instability, Thailand has neither fulfilled its promise to ratify the

treaty nor has it resolved the case of disappeared lawyer, Somchai

Neelaphaijit and many other cases in the south as well as those stemming

from the 1992 Black May massacre.

Nepal, the country that submitted the most number of

cases to the UNWGEID in 2004, also drafted a bill criminalizing

disappearances. On 5 February 2009, the bill was approved in a form of an

Ordinance. According to the Nepali civil society, it is questionable in

terms of process and substance. The Advocacy Forum and the rest of the

civil society work hard to ensure that this Ordinance be transformed into

an Act of Parliament and that its provisions respond to the needs of the

families of the disappeared. The Nepali government has no clear position

on the Convention. If and when the process and the substance of the bill

penalizing disappearances be corrected so as to respond to the needs of

the victims, it is but proper that Nepal should be one of the first

countries, if not the first country in Asia to ratify the treaty.

In Asia, the task of lobbying for signatures and

ratifications is an uphill battle. The AFAD member-organizations’ efforts

are only answered by governments with diplomatic promises of studying

further the Convention, consulting other government agencies and

eventually ratifying it “in due time.” Whatever “due time,” means, we

never know. It could be waiting forever …

Revisiting our Lobbying Strategies…

This alarming absence of Asian ratifications calls on

the AFAD to reevaluate the Asian situation, re-assess governments’

attitudes vis-à-vis disappearances; check on the internal strengths and

weaknesses in intensifying the lobbying efforts and in terms of the

cooperation and/or lack of cooperation of other actors at the regional and

international levels.

During

the treaty’s drafting and negotiation process, the AFAD played a major

role in convincing the UN to adopt it. How could this role be sustained at

this stage when the challenge for intensive lobbying lies at the national

level? The role of national organizations, in cooperation with other

actors, is crucial. A process of internal strengthening coupled with sharp

strategizing is important to guarantee a strong impact.

During

the treaty’s drafting and negotiation process, the AFAD played a major

role in convincing the UN to adopt it. How could this role be sustained at

this stage when the challenge for intensive lobbying lies at the national

level? The role of national organizations, in cooperation with other

actors, is crucial. A process of internal strengthening coupled with sharp

strategizing is important to guarantee a strong impact.

Most ratifications come from Latin American

governments, in their explicit admission of their dark history of

disappearances. The Asian governments equally have the moral

responsibility to sign and ratify the treaty. In a region that despite

governments’ denial is haunted by the ever-spiritual presence of

desaparecidos, the apt call is: Convention Now: Respect the Right Not

to Disappear.

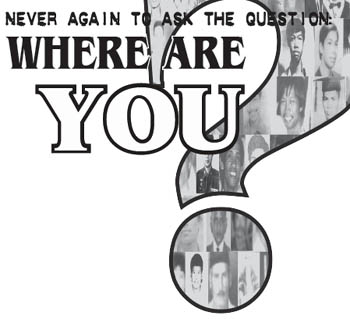

If entered into force, the treaty guarantees that no

more Macarenas and many other children, wives, husbands, sisters, brothers

of the disappeared will again ask the nagging question, “Where are you?”

What contribution can we concretely give to stop this

scourge?

___________________________

End note:

1 Excerpt from the presentation of Gimena Gomez, the

person in-charge of the Latin American Federation of Associations of

Relatives of Disappeared-Detainees’ (FEDEFAM’s) International

Relations in a joint parallel event conducted by the AFAD and FEDEFAM

during the March 2009 session of the UN Human Rights Council held in

Geneva, Switzerland. The excerpt has been translated from Spanish to

English.

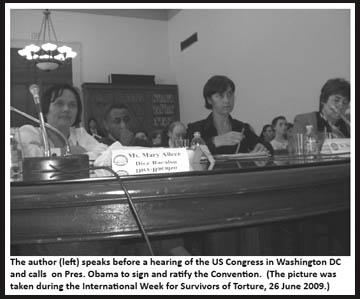

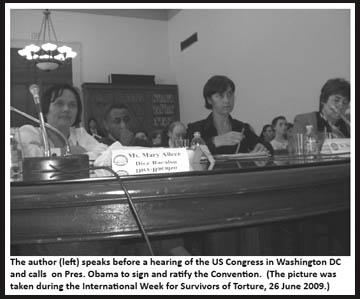

Mary Aileen Diez-Bacalso is currently the

Secretary-General of the AFAD. Her most outstanding contribution to the

fight against impunity was her active participation in the three-year

drafting and negotiation process of the UN Convention for the Protection

of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

The

Convention also recognizes the right to know the truth about the

circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of

the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person. As Atty. Citroni

further said, providing for this right is the first instance that has

occurred in international human rights law.

The

Convention also recognizes the right to know the truth about the

circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of

the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person. As Atty. Citroni

further said, providing for this right is the first instance that has

occurred in international human rights law. That

the Convention enters into force without delay and that it be implemented

universally are moral obligations of states. In all nooks and corners of

the world, enforced disappearances continue to steal precious lives. The

United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances

(UNWGEID) reported during the 10th session of the UN Human Rights Council

in March 2009 that: “The total number of cases transmitted by the Working

Group to Governments since its inception is 52,952. The number of cases

under active consideration that have not yet been clarified, closed and

discontinued stands at 42,393 and concerns 79 States….” Of the 79 states,

21 are Asian.

That

the Convention enters into force without delay and that it be implemented

universally are moral obligations of states. In all nooks and corners of

the world, enforced disappearances continue to steal precious lives. The

United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances

(UNWGEID) reported during the 10th session of the UN Human Rights Council

in March 2009 that: “The total number of cases transmitted by the Working

Group to Governments since its inception is 52,952. The number of cases

under active consideration that have not yet been clarified, closed and

discontinued stands at 42,393 and concerns 79 States….” Of the 79 states,

21 are Asian. Looking

back to the AFAD’s visit to this so-called “Pearl of the Indian Ocean” and

“Paradise Island,” this writer recalls the families of the disappeared

whose loved ones disappeared in the nineties and endlessly clamored for

truth about their disappearance. They told stories of their kin who never

saw light at the end of the tunnel and ended up committing suicide.

Looking

back to the AFAD’s visit to this so-called “Pearl of the Indian Ocean” and

“Paradise Island,” this writer recalls the families of the disappeared

whose loved ones disappeared in the nineties and endlessly clamored for

truth about their disappearance. They told stories of their kin who never

saw light at the end of the tunnel and ended up committing suicide. Many

similar stories of woes originate in Afghanistan, Burma, China, East

Timor, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and several other

Asian countries. These make us wonder why is it that in this supposedly

civilized world and despite the membership of a number of these countries

in the prestigious UN Human Rights Council, disappearances and many other

forms of human rights violations continue to be the order of the day. They

speak of lives lost, hearts broken, families, communities and the greater

society devastated by this crime against humanity.

Many

similar stories of woes originate in Afghanistan, Burma, China, East

Timor, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand and several other

Asian countries. These make us wonder why is it that in this supposedly

civilized world and despite the membership of a number of these countries

in the prestigious UN Human Rights Council, disappearances and many other

forms of human rights violations continue to be the order of the day. They

speak of lives lost, hearts broken, families, communities and the greater

society devastated by this crime against humanity. The

Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) has made

numerous efforts to convince governments of Thailand, Indonesia, the

Philippines, Sri Lanka and Nepal to ratify the Convention. Concrete

efforts were accomplished through the series of fora on the Convention,

meetings with government agencies, distribution of campaign materials,

etc. At the international level, letters calling on governments worldwide

to ratify the Convention have been sent.

The

Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) has made

numerous efforts to convince governments of Thailand, Indonesia, the

Philippines, Sri Lanka and Nepal to ratify the Convention. Concrete

efforts were accomplished through the series of fora on the Convention,

meetings with government agencies, distribution of campaign materials,

etc. At the international level, letters calling on governments worldwide

to ratify the Convention have been sent. During

the treaty’s drafting and negotiation process, the AFAD played a major

role in convincing the UN to adopt it. How could this role be sustained at

this stage when the challenge for intensive lobbying lies at the national

level? The role of national organizations, in cooperation with other

actors, is crucial. A process of internal strengthening coupled with sharp

strategizing is important to guarantee a strong impact.

During

the treaty’s drafting and negotiation process, the AFAD played a major

role in convincing the UN to adopt it. How could this role be sustained at

this stage when the challenge for intensive lobbying lies at the national

level? The role of national organizations, in cooperation with other

actors, is crucial. A process of internal strengthening coupled with sharp

strategizing is important to guarantee a strong impact.