A glimmer of hope offered by the government’s

initiative to make public a draft bill for the formation of a Commission

on Disappearance eventually turned out to be a sheer anticlimax with an

unexpected second thought on 5 February 2009 by the cabinet to form the

aforesaid commission via an ordinance. Among other things, the passing of

the disappearance ordinance to form a Commission on Disappearances has

served as a major blow towards efforts by all parties concerned in

investigating and making public the whereabouts of thousands of Nepali

citizens who have disappeared over the decade-long armed conflict.

Although, the argument is that this ordinance would actually expedite the

process of establishment of the Disappearance Commission and help bring

the peace process to a ‘meaningful conclusion,’ there are issues of

greater importance which must be paid attention to before taking to this

road.

The

basic theory behind passing an ordinance is to enforce legislation during

a parliamentary recess to deal with some emergency situations or address

some issues of prime importance. Passing of ordinances as such are not an

undemocratic phenomenon but it is also critical, in the event of such

situations that the government honors the sanctity of such ordinances

while drafting them so that they will not turn out to be apples of

discord. However, the government has failed to observe both of these

niceties and other issues while issuing the disappearance ordinance.

The

basic theory behind passing an ordinance is to enforce legislation during

a parliamentary recess to deal with some emergency situations or address

some issues of prime importance. Passing of ordinances as such are not an

undemocratic phenomenon but it is also critical, in the event of such

situations that the government honors the sanctity of such ordinances

while drafting them so that they will not turn out to be apples of

discord. However, the government has failed to observe both of these

niceties and other issues while issuing the disappearance ordinance.

First, the government has itself made the circumstances

extenuating. The draft bill for the formation of a Disappearance

Commission was unveiled on 15 November 2008 and was simultaneously

approved by the Cabinet four days later. The parliamentary session was

running smoothly then and continued for the next one month and a half. But

the government, for unknown reasons, did not table it for endorsement.

Following the adjournment of the parliamentary session, the government

sent the ordinance to the president on 10 February 2009 for the seal of

assent.

The reasons put forward by the government in connection

with the ordinance move are to expedite the process of establishment of

the Disappearance Commission and to help bring the peace process to a

‘meaningful conclusion. ’Such justifications are surely not bona fide

as the government surprisingly shrugged off the issue by not tabling it in

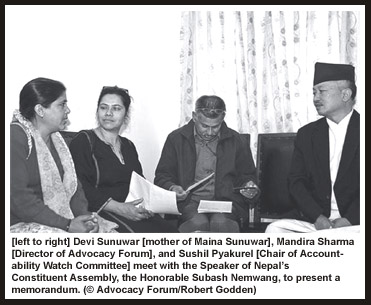

the parliament. In the midst of this, the Constituent Assembly (CA)

Speaker and the Chairman of National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) flatly

denied, citing the ordinance as not bearing democratic temper, assuming

their designated role as panelists in the selection committee for

commissioners.

Second,

the ordinance is fraught with many flaws and gaps. It is an inchoate

instrument with a number of provisions and sections not on par with

international standards. There are neither provisions regarding the issue

of deliberate disappearance nor on clarity about the investigating

authority. A number of human rights organizations had put forward their

suggestions regarding these deficiencies when the ordinance was still a

draft. Moreover, these organizations had also raised concerns over the

ordinance’s legitimacy.

Second,

the ordinance is fraught with many flaws and gaps. It is an inchoate

instrument with a number of provisions and sections not on par with

international standards. There are neither provisions regarding the issue

of deliberate disappearance nor on clarity about the investigating

authority. A number of human rights organizations had put forward their

suggestions regarding these deficiencies when the ordinance was still a

draft. Moreover, these organizations had also raised concerns over the

ordinance’s legitimacy.

The government’s passing of laws and forming of

commissions via ordinances only a few days after the legislative

parliament was adjourned beget serious questions on its intentions. These

moves cannot be justified under any circumstances let alone in the name of

the peace process, especially given that the commissions formed in the

past without any public consultations have failed to deliver outputs

vis-à-vis their objectives and have only led to the further

institutionalization of impunity in Nepal. Hence, it is of utmost

importance that we rectify the mistakes of the past which have, to a

certain extent, contributed to the problems faced by the country. It is

important that we set a positive precedent whereby we follow a proper

process which is democratic and which leads to a sustainable and

meaningful peace in the country.

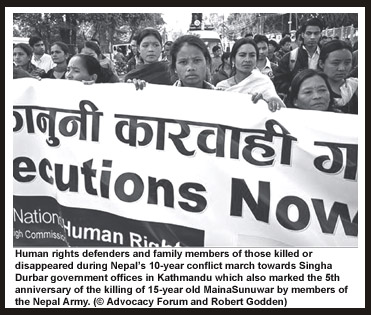

Moreover, several problems have surfaced in the wake of the ordinance

promulgation. If the commission on disappearances is indeed formed through

the ordinance, the legitimacy of the commission will be at risk. Such then

would be further counterproductive, especially given that the process has

already become controversial and has been criticized not only by national

actors, including the political parties but also international

organizations such as Amnesty International,

Human Rights Watch, International Commission of Jurists and others. The

formation of the peace bodies such as the Disappearance Commission needs

to be discussed widely. There has to be a political consensus for such

bodies to become legitimate and effective. The current political

controversy surrounding the process of introducing the legislation poses

major risks to its effectiveness and legitimacy.

Now

that the cabinet has passed the ordinance on forming a disappearance

commission and that such ordinance has been approved by the President, it

will still have to be tabled at the next session of the Legislative

Parliament and passed by it. If not passed, it would ipso facto

cease to be effective [Section 88 of the Interim Constitution]. This would

pose serious risks if the House fails to pass this law when it is tabled.

Under such circumstances, the work of the commission during its

functioning with all the efforts to make public the whereabouts of the

disappeared and bring perpetrators to justice would be jeopardized.

Now

that the cabinet has passed the ordinance on forming a disappearance

commission and that such ordinance has been approved by the President, it

will still have to be tabled at the next session of the Legislative

Parliament and passed by it. If not passed, it would ipso facto

cease to be effective [Section 88 of the Interim Constitution]. This would

pose serious risks if the House fails to pass this law when it is tabled.

Under such circumstances, the work of the commission during its

functioning with all the efforts to make public the whereabouts of the

disappeared and bring perpetrators to justice would be jeopardized.

Apparently, there is a catch-22 situation. Even after being tabled in the

parliament, the ordinance needs either to be approved or disapproved. The

Communist Party of Nepal – United Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML), a partner in

the coalition government as well as the main opposition party of the

Nepali Congress had already cried foul over the intentions of the

government vis-à-vis the issuance of the ordinance. If these parties

opposed, the ordinance will automatically be rendered null and void. This

will also help the Maoists, who are claiming that the other parties are

not interested in the formation of a commission, to derelict their

responsibilities. The accruing consequences might lead to an impasse in

the formation of the commission, which will nip the optimism of thousands

of family members of the disappeared in the bud.

The general feeling is that the government intends to form the commission

even before the ordinance is tabled at the next session of the parliament.

We need to take a stance whereby the government starts the process of the

selection and appointment of commissioners and other initial work only

after the ordinance has been tabled and passed by the legislative

parliament. As the functioning and the work of the commission may become

useless if the legislative parliament fails to pass the ordinance, it is a

must that the legislative parliament approves the bill before the major

work starts. Without this, the situation will jeopardize all the efforts

to make public the whereabouts of the disappeared people and give justice

to the victims and their families.

If the government goes ahead and forms the commission

before the ordinance is tabled at the legislative parliament; when the

ordinance is actually tabled (as per section 88 of the interim

constitution) and law makers raise issues with regards to the bill and

discussions start, there are three possible scenarios we may find

ourselves in:

• As discussed earlier, the work of the commission may

become useless if the legislative parliament fails to pass the ordinance.

This will just derail the process of the formation of the Commission and

passing of the law to criminalize disappearances.

• The discussion on the ordinance may last from a week

to months (even if a single member of the parliament disagrees to pass the

bill, it has to be sent to a special committee to be reviewed). Till this

time, the commission may either have already started and accomplished a

major portion of its tasks or has already completed its work. Hence, the

chance to rectify the flaws in the bill and form a commission via a

legitimate process will have been missed.

• Mainly, if formed under such circumstances, it will

also prevent another commission on disappearance to be formed as per

section 38 (2) of the ordinance where it states that no other commission

may be formed to investigate the same cases of disappearances in the

future once a commission has been formed to investigate disappearances.

Therefore,

there is an urgent need to seek avenues out so that the problem could be

solved through a remedial consensus. One of the easiest ways out of this

possible stalemate is calling for a special session of the parliament to

discuss the ordinance. The interim constitution has a provision whereby

one fourth of the majority can call for a special session of the

legislative parliament. When this option still existed, there was no

reason for the government and the political parties not to invoke this

provision. The government and the political parties should have come to a

consensus to invoke this provision and call for a special session of the

House where the law on disappearances along with other laws can be tabled

and passed after scrutinizing these bills in a democratic manner.

Therefore,

there is an urgent need to seek avenues out so that the problem could be

solved through a remedial consensus. One of the easiest ways out of this

possible stalemate is calling for a special session of the parliament to

discuss the ordinance. The interim constitution has a provision whereby

one fourth of the majority can call for a special session of the

legislative parliament. When this option still existed, there was no

reason for the government and the political parties not to invoke this

provision. The government and the political parties should have come to a

consensus to invoke this provision and call for a special session of the

House where the law on disappearances along with other laws can be tabled

and passed after scrutinizing these bills in a democratic manner.

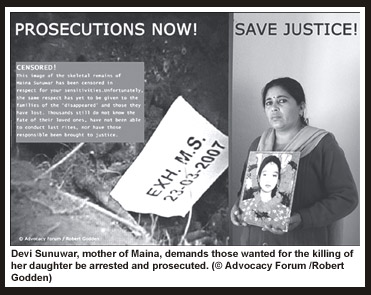

Further, a substitute ordinance drafted in line with the international

standards can be tabled and discussed in the House. The crucial question

is not whether the ordinance is democratic or not. The commission to be

formed via this ordinance is linked to the future of the victims, who are

waiting with bated breath for a fair hearing of their pain. On all costs,

the victims’ family members should be given the opportunity of selecting

the commissioners. This will not only increase their respect for the

government but also set a good precedent that even an ordinance could be

treated well and subsequently be entrenched in the form of proper

legislation.

The

basic theory behind passing an ordinance is to enforce legislation during

a parliamentary recess to deal with some emergency situations or address

some issues of prime importance. Passing of ordinances as such are not an

undemocratic phenomenon but it is also critical, in the event of such

situations that the government honors the sanctity of such ordinances

while drafting them so that they will not turn out to be apples of

discord. However, the government has failed to observe both of these

niceties and other issues while issuing the disappearance ordinance.

The

basic theory behind passing an ordinance is to enforce legislation during

a parliamentary recess to deal with some emergency situations or address

some issues of prime importance. Passing of ordinances as such are not an

undemocratic phenomenon but it is also critical, in the event of such

situations that the government honors the sanctity of such ordinances

while drafting them so that they will not turn out to be apples of

discord. However, the government has failed to observe both of these

niceties and other issues while issuing the disappearance ordinance. Second,

the ordinance is fraught with many flaws and gaps. It is an inchoate

instrument with a number of provisions and sections not on par with

international standards. There are neither provisions regarding the issue

of deliberate disappearance nor on clarity about the investigating

authority. A number of human rights organizations had put forward their

suggestions regarding these deficiencies when the ordinance was still a

draft. Moreover, these organizations had also raised concerns over the

ordinance’s legitimacy.

Second,

the ordinance is fraught with many flaws and gaps. It is an inchoate

instrument with a number of provisions and sections not on par with

international standards. There are neither provisions regarding the issue

of deliberate disappearance nor on clarity about the investigating

authority. A number of human rights organizations had put forward their

suggestions regarding these deficiencies when the ordinance was still a

draft. Moreover, these organizations had also raised concerns over the

ordinance’s legitimacy. Now

that the cabinet has passed the ordinance on forming a disappearance

commission and that such ordinance has been approved by the President, it

will still have to be tabled at the next session of the Legislative

Parliament and passed by it. If not passed, it would ipso facto

cease to be effective [Section 88 of the Interim Constitution]. This would

pose serious risks if the House fails to pass this law when it is tabled.

Under such circumstances, the work of the commission during its

functioning with all the efforts to make public the whereabouts of the

disappeared and bring perpetrators to justice would be jeopardized.

Now

that the cabinet has passed the ordinance on forming a disappearance

commission and that such ordinance has been approved by the President, it

will still have to be tabled at the next session of the Legislative

Parliament and passed by it. If not passed, it would ipso facto

cease to be effective [Section 88 of the Interim Constitution]. This would

pose serious risks if the House fails to pass this law when it is tabled.

Under such circumstances, the work of the commission during its

functioning with all the efforts to make public the whereabouts of the

disappeared and bring perpetrators to justice would be jeopardized. Therefore,

there is an urgent need to seek avenues out so that the problem could be

solved through a remedial consensus. One of the easiest ways out of this

possible stalemate is calling for a special session of the parliament to

discuss the ordinance. The interim constitution has a provision whereby

one fourth of the majority can call for a special session of the

legislative parliament. When this option still existed, there was no

reason for the government and the political parties not to invoke this

provision. The government and the political parties should have come to a

consensus to invoke this provision and call for a special session of the

House where the law on disappearances along with other laws can be tabled

and passed after scrutinizing these bills in a democratic manner.

Therefore,

there is an urgent need to seek avenues out so that the problem could be

solved through a remedial consensus. One of the easiest ways out of this

possible stalemate is calling for a special session of the parliament to

discuss the ordinance. The interim constitution has a provision whereby

one fourth of the majority can call for a special session of the

legislative parliament. When this option still existed, there was no

reason for the government and the political parties not to invoke this

provision. The government and the political parties should have come to a

consensus to invoke this provision and call for a special session of the

House where the law on disappearances along with other laws can be tabled

and passed after scrutinizing these bills in a democratic manner.