Clad

in red, the symbol of marital bliss and sanctity in Hindu culture of

Nepal, and with a faint glimmer of hope in their eyes, they have been

moving from pillar to post to find the whereabouts of their husbands. It

has been ages since these women last saw their husbands. Their misty eyes

show signs of eternal waiting for the eventual return of their disappeared

loved ones.

Clad

in red, the symbol of marital bliss and sanctity in Hindu culture of

Nepal, and with a faint glimmer of hope in their eyes, they have been

moving from pillar to post to find the whereabouts of their husbands. It

has been ages since these women last saw their husbands. Their misty eyes

show signs of eternal waiting for the eventual return of their disappeared

loved ones.

Have those disappeared already been killed? A

disappeared cannot be pronounced dead till their remains are found. To

live in dilemma, undoubtedly is more than being crucified. When will the

status of the disappeared during the decade-long conflict in the country

be established? When will their loved ones return? These questions are

gnawing their spirits and killing them softly.

On the one hand, the Nepali women have been waging a

war against discrimination to achieve equality and social justice. On the

other hand, they have to bear the brunt of the decade-long conflict in the

country. The socio-economic-cultural structure of the country endows a

secondary role to women. They have no separate identity besides literally

playing the second fiddles in the affairs of society. For them, their

“valiant halves” are the Almighty Gods, on whose mercy the entire drama of

their lives unfolds.

“I

have completely no desire to live, I could neither feed my children; the

bringer of bacon is still missing. Nor could I provide them with the

proper education and feed them well. I feel like killing my children and

committing suicide than just dragging on through this unfeeling world.

Sometimes I tried to feel what my husband would possibly say to me if we

meet again. A decade-long separation, I can’t imagine! I believe that

everything will never be the same again if he comes back. Sometimes, I

feel suffocated by my inability to manage my family. But the hope always

lurks behind my every thought and I just manage to wade on.”

“I

have completely no desire to live, I could neither feed my children; the

bringer of bacon is still missing. Nor could I provide them with the

proper education and feed them well. I feel like killing my children and

committing suicide than just dragging on through this unfeeling world.

Sometimes I tried to feel what my husband would possibly say to me if we

meet again. A decade-long separation, I can’t imagine! I believe that

everything will never be the same again if he comes back. Sometimes, I

feel suffocated by my inability to manage my family. But the hope always

lurks behind my every thought and I just manage to wade on.”

The innocents got meshed up in the whirlpool of conflict and emerged,

ultimately, as victims. Although the country underwent a massive political

transformation and the erstwhile rebels are basking in the afterglow of

their ascent to power, the situation of the victims remains as it was

during the period of the conflict. The so-called architects of New Nepal

are enjoying every physical amenity available in the market but are

negligent of the daily needs of the victims. What ails most is that they

are still putting a blind eye towards establishing the status of the

disappeared.

“I am hopeful for his return. I exist just because I am

optimistic about his arrival. He haunts me in my dreams and says that he

is coming soon. I sometimes feel that he is walking by my side. If I

happen to encounter someone who is of my husband’s stature or wears

clothes like him, I mistake the stranger as my beloved. He will certainly

come because he was innocent. The killers are walking freely. The people

in the government do nothing but criticize the older establishment for the

latter’s myopic vision and tyranny. But they don’t care about us, victims.

Those who are running the government now are the ones who started an armed

revolution to do away with injustice and discrimination. However, they are

busy only in visiting foreign lands and providing employment to their

yes-men. They don’t have time even to spare a minute to listen to the woes

of the victims. The abduction and disappearance of people are still

continuing. The list of the victims is increasing and more and more people

are suffering from the same problems we endured during the conflict. “

“Hordes of people were disappeared but nobody knows

their whereabouts. This work has tremendous repercussions on the lives of

people making our life literally a hell. Life is really absurd for us. The

children inquire about their father and I am forced to invent lies that he

will be back in a month or two. I always remember him. A day never passes

without remembering him. I am angry with the people who keep on coming in

flocks to record the incidents; hundreds came and documented the case but

none has ever informed me about the status of my husband. I have lost all

hopes. I am illiterate and I know nothing. If you could show me the way, I

will be obliged to you all my life. I feel like committing suicide. What

shall I do? “

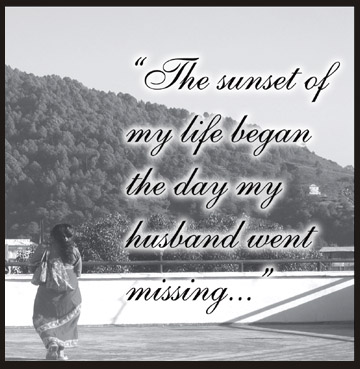

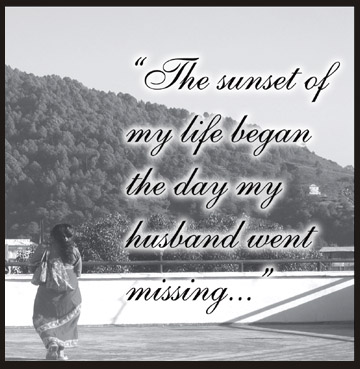

“The sunset of my life began the day my husband went

missing. I don’t know how I am living without him. In the midst of this,

my-mother-in-law, father-in-law, sister-in-law hate me. “If we don’t have

a brother at home, what is my use? You are just a jinxed woman and he

disappeared because of this,” my mother-in- law said this a week ago. I

spent the whole night weeping. Unable to resist more with my suicidal

thoughts, I went to nearby Trishuli River to get drowned but I remembered

the advice of sisters like me. I remembered my daughters and came back. My

relatives in-law had planned to send my daughters to my parents’ house

after I get drowned and when they saw me coming back, they scolded me and

asked where I had been and with whom I was with for being so late.

Remembering my husband’s love for me, I tried to be indifferent and

unmindful of their behavior. Ours was a love marriage and he was the sole

breadwinner of the family. I am worried about the future of my daughters.

I can’t leave this place because what would my husband say if he returns

back. The dilemma is killing me. “

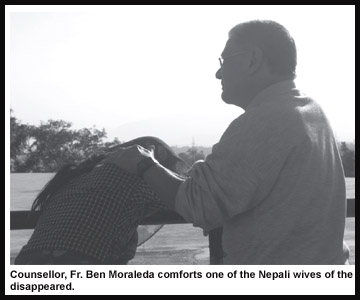

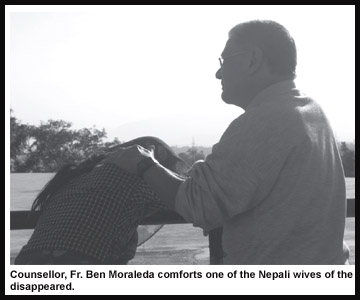

The above-mentioned excerpts are a part of the pain

reported by the wives of the disappeared. I have been doing a thorough

psychoanalytical reading of such stories of deepest pain verbalized by the

victims. My analysis shows that the continual mental affliction of the

wives of the disappeared, if not attended, might burst into some kind of

violence which could be costly and detrimental to society.

Note: I did not mention the names of the victims,

since the stories are almost the same as those of thousands

of other wives of the disappeared.

A lawyer by profession, Kopila Adhikari leads the human rights

documentation unit of Advocacy Forum, one of Nepal’s leading

non-government organizations which has joined the AFAD. She represents her

organization at the AFAD Council.

Clad

in red, the symbol of marital bliss and sanctity in Hindu culture of

Nepal, and with a faint glimmer of hope in their eyes, they have been

moving from pillar to post to find the whereabouts of their husbands. It

has been ages since these women last saw their husbands. Their misty eyes

show signs of eternal waiting for the eventual return of their disappeared

loved ones.

Clad

in red, the symbol of marital bliss and sanctity in Hindu culture of

Nepal, and with a faint glimmer of hope in their eyes, they have been

moving from pillar to post to find the whereabouts of their husbands. It

has been ages since these women last saw their husbands. Their misty eyes

show signs of eternal waiting for the eventual return of their disappeared

loved ones. “I

have completely no desire to live, I could neither feed my children; the

bringer of bacon is still missing. Nor could I provide them with the

proper education and feed them well. I feel like killing my children and

committing suicide than just dragging on through this unfeeling world.

Sometimes I tried to feel what my husband would possibly say to me if we

meet again. A decade-long separation, I can’t imagine! I believe that

everything will never be the same again if he comes back. Sometimes, I

feel suffocated by my inability to manage my family. But the hope always

lurks behind my every thought and I just manage to wade on.”

“I

have completely no desire to live, I could neither feed my children; the

bringer of bacon is still missing. Nor could I provide them with the

proper education and feed them well. I feel like killing my children and

committing suicide than just dragging on through this unfeeling world.

Sometimes I tried to feel what my husband would possibly say to me if we

meet again. A decade-long separation, I can’t imagine! I believe that

everything will never be the same again if he comes back. Sometimes, I

feel suffocated by my inability to manage my family. But the hope always

lurks behind my every thought and I just manage to wade on.”