Now in Argentina, almost 30 years after atrocious human rights crimes

were committed, we have human rights trials going on which the practice

of enforced disappearances is concretely investigated and perpetrators

are brought before the courts. While other Latin American countries

which went through similar experiences in the seventies and eighties,

have preferred the road of national reconciliation, Argentina is at the

forefront in prosecuting perpetrators and provides an interesting case

study and a cause for hope among human rights activists around the

world.

Background

Argentina is known as the world’s granary because of

its immense natural resources but really is on the margin of world

affairs in the Southern Hemisphere despite its strongly European

population, unlike Australia and New Zealand in Asia Pacific. However,

it really is not different from other Latin American countries where a

small oligarchic group came to own most of its wealth that was

forcefully taken from the native peoples in Spanish colonial times. Even

after the final extermination campaigns of native Argentines were ended

in the Patagonia and the Tropical north, towards the end of the XIX

century, that land was handed over to the traditional elite, and the

immigrant population had no option but to stay in the cities. The

country was destined to produce and export raw materials but not to

industrialize or manufacture any goods. There were several attempts to

break this deadlock through industrialization, the most famous being the

government of Juan Domingo Peron and his charismatic wife Eva in the

late 1940s, but all ended with military coups and repression. Then in

the sixties, Argentine youth, inspired by Che Guevara and other

revolutionaries, many within the Peronist movement, organized to produce

the social change that was needed to overcome longstanding structural

violence. This way of revolutionary struggle was met by the violence of

the State now known as ‘State terrorism’ which reached its pinnacle with

the Junta Dictatorship (1976 – 83). The cornerstone of State terrorism

was the practice of enforced disappearance, but it took many years

before the full dimension of what was clandestinely going on was finally

brought to the public light. The key players were the families of the

disappeared, especially the Madres of Plaza de Mayo.

Why such a strong sentiment for justice in Argentina?

Certain events in recent Argentine history may

explain the strong national sentiment towards justice.

The

first and most important element is the nature of the crime involved,

i.e., enforced disappearance. Here, official cynicism was the order of

the day as the demand to know the whereabouts of a loved one was

routinely dismissed by the authorities, or relatives of the victim were

blackmailed into giving money and property for information which

effectively always proved to be without substance. Then relatives

themselves became victims. This situation went on for many years and

created such a deeply-rooted sentiment of resentment towards impunity

that exasperates itself with the passage of time.

The

first and most important element is the nature of the crime involved,

i.e., enforced disappearance. Here, official cynicism was the order of

the day as the demand to know the whereabouts of a loved one was

routinely dismissed by the authorities, or relatives of the victim were

blackmailed into giving money and property for information which

effectively always proved to be without substance. Then relatives

themselves became victims. This situation went on for many years and

created such a deeply-rooted sentiment of resentment towards impunity

that exasperates itself with the passage of time.

The

second reason is that when the dictatorship was nearing its end, it

decided in 1982 to initiate a patriotic war against the UK in order to

recover sovereignty over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands and to recover

prestige. However, there were many losses. Argentina lost the war and

people felt totally betrayed by the military. Since then, the Armed

Forces lost their status in society. There is therefore, little sympathy

when former senior officers are brought into courts.

The

second reason is that when the dictatorship was nearing its end, it

decided in 1982 to initiate a patriotic war against the UK in order to

recover sovereignty over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands and to recover

prestige. However, there were many losses. Argentina lost the war and

people felt totally betrayed by the military. Since then, the Armed

Forces lost their status in society. There is therefore, little sympathy

when former senior officers are brought into courts.

From Human Rights Crimes to Impunity to Justice

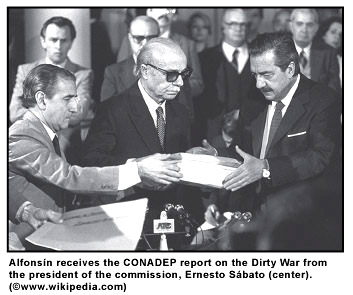

1984: The CONADEP Commission - After the

late President Raul Alfonsin became democratic president at the end of

1983, this presidential commission was appointed to investigate the case

of the desaparecidos. The result was the "Never Again"

report presented by writer Ernesto Sabato, which fully documented

the enforced disappearances with the different circuits of secret

detention centers, clandestine cemeteries and military task forces.

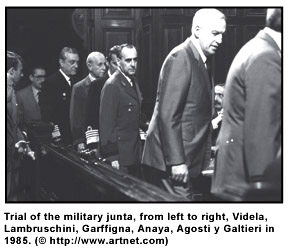

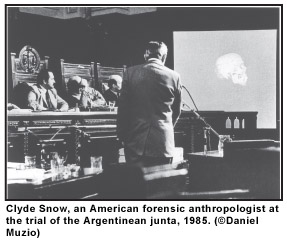

1985: The Argentine Junta Trial - For the first

time ever in Latin America, top military leaders, the Junta were charged

before a civilian court and condemned to long sentences of imprisonment

for multiple human rights violations, above all, the enforced

disappearances. Due to the nature of the crimes involved, the Court

recommended the prosecution of all perpetrators down the line of

command.

1986 First Impunity Law - Final Point Law The

military mobilized against those prosecutions and President Alfonsín

gave in. A law was approved at the end of 1986 which gave a deadline for

presenting new human rights cases. The immediate result was that

hundreds of new cases were rushed into the courts to meet that deadline

and many more military people were implicated.

1987 Second Impunity Law - Due Obedience Law The

military began to openly rebel against the prosecutions, and to occupy

military establishments in defiance of the democratic government.

Finally, President Alfonsin negotiated and the Due Obedience Law was

passed by Congress. That meant that only the top command structure could

be charged for human rights violations and all the other cases had to be

dropped. There was an exception – the case of disappeared children.

1990 Third Impunity Measures - Presidential Pardons. The new

President Carlos Menem (1989 -1990) decided on a pacification process

where reparation would be given to victims but penal prosecutions would

be discontinued. There were a series of presidential pardons granted so

that by the end of 1991, even those sentenced in the Junta Trials, were

released.

1992 Argentine Trials in Europe and Universal

Jurisdiction.

With impunity reigning in the county, families and

the human rights organizations began to promote trials in European

countries whose citizens had been victims of the Argentine dictatorship.

As there was no possibility of prosecution in Argentina, those penal

processes had become perfectly legal. So cases were opened in Sweden,

France, Italy, Germany and above all Spain where Judge Baltasar Garzon

began to also use the argument of universal jurisdiction whenever crimes

against humanity were involved. According to universal jurisdiction,

when impunity exists for a crime against humanity in a specific country,

any other country can claim jurisdiction to prosecute perpetrators.

Enforced disappearance is a crime against humanity. This led to Judge

Garzon issuing an arrest warrant in 1994 against former Chilean dictator

Augusto Pinochet who was visiting London. Pinochet was arrested and

returned to Chile on humanitarian grounds. However, the UK House of

Lords had recognized the Garzon petition as valid. Many new arrest

warrants were issued against Argentine perpetrators so much that towards

the end of the ninetees, none could safely leave the country. However

the Menem government absolutely refused to extradite any military

officer to Spain. Simultaneously both the Inter American Human Rights

Commission and Court intervened and ruled that the Argentine impunity

laws went against the principles of international law.

Prosecutions for the Disappeared Children Continue

In Argentina, the cases for the disappeared children

could however, continue and it was successfully argued in court that

such a practice had in fact been endorsed at the top command structure

of the Armed Forces. In that way the Junta leaders found themselves back

in prison under new charges.

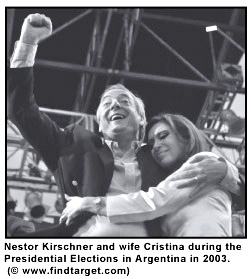

Triumph of the Anti-Impunity Movement

Between 2000 and 2003, Argentina went through a

period of total economic collapse. Finally in 2003, Mr. Nestor Kirchner

was elected President. He surprised many by taking a very strong pro

human rights position and among other measures began to argue for the

absolute nullity of the impunity laws and for the continuation of the

human rights trials which had been halted in 1987. Finally, the military

accepted that policy as they preferred to be prosecuted in Argentina

rather than extradited to Spain. Meanwhile President Kirchner achieved

an important reform of the Supreme Court. A law was approved by Congress

nullifying all the impunity laws, and in a historic decision in 2005,

the Supreme Court certified their absolute nullity. The human rights

trials were reinitiated.

How do the human rights trials work?

To begin with in these trials, those who have been

personally affected by the crimes involved can participate as part of

the prosecution. That means that victims are directly involved. Many

human rights organizations have recruited young lawyers to work in the

courtrooms to represent the victims. According to the Argentine judicial

system, there are two stages in the penal process. The Instruction

stage is when a specific crime is investigated, perpetrators are

identified and written testimonies taken from witnesses. All parts

intervene and defendants may be imprisoned. A special prison was opened

in Marcos Paz, Buenos Aires Province where perpetrators of human rights

violations are held. Those who are older than seventy can be allowed the

benefit of home arrest. This is also granted to those with serious

health problems and some argue senility to avoid prosecution.

The

Instruction finishes with the formal accusation which is handed over to

a Federal Court where the Public and Oral trial takes place. This

is the second and final stage which usually goes for several months.

This process opens with the formal indictment of the defendants who must

appear in court. It is then when families can see them for the first

time. Then witnesses are called in to give their testimony and answer

questions both of the prosecution (including representatives of the

victims) and the defense. Forensic or other experts address the court

and the defense may also call other witnesses. Finally there is the

summing up of the parts. On the last day of the public hearings, the

defendants are allowed to make their final statement and then the judges

(usually three) give their verdict. About two weeks afterwards, the

court is convened again when the full sentence is out. Finally the

entire proceedings automatically go for review to the higher Cassation

Court which makes a final legal ruling on the proceedings. That

may take a year or more. The case can then be appealed to the Supreme

Court but that has rarely, if at all, happened.

The

Instruction finishes with the formal accusation which is handed over to

a Federal Court where the Public and Oral trial takes place. This

is the second and final stage which usually goes for several months.

This process opens with the formal indictment of the defendants who must

appear in court. It is then when families can see them for the first

time. Then witnesses are called in to give their testimony and answer

questions both of the prosecution (including representatives of the

victims) and the defense. Forensic or other experts address the court

and the defense may also call other witnesses. Finally there is the

summing up of the parts. On the last day of the public hearings, the

defendants are allowed to make their final statement and then the judges

(usually three) give their verdict. About two weeks afterwards, the

court is convened again when the full sentence is out. Finally the

entire proceedings automatically go for review to the higher Cassation

Court which makes a final legal ruling on the proceedings. That

may take a year or more. The case can then be appealed to the Supreme

Court but that has rarely, if at all, happened.

The cases involved refer to very specific crimes in

the penal code such as homicide, illegal arrest, torture etc. (enforced

disappearance or genocide is not listed). For a guilty verdict, criminal

responsibility has to be proved beyond doubt. If not, the defendant will

be acquitted. The sessions are public so anyone can attend the hearings

and sometimes the media are allowed in, but in most cases, there are

restrictions. It all depends on the court.

To facilitate the process, cases are divided

according to the five military divisions of Argentina applied during the

dictatorship. Usually cases are identified and grouped with specific

secret detentions centers. Some secret detention centers are so big that

the category of "mega cases" had to be created. These mega cases are

sometimes divided down for trial purposes.

Completed Cases:

The following list of completed cases shows how the

process is working:

2006: Buenos Aires: Former Federal police officer

Julio Hector Simon was condemned for several human rights crimes.

2007:

La Plata: Miguel Etchcolatz , former head of the secret police in

the Province of Buenos Aires was condemned for 5 cases of homicide and

torture. It was during his trial that an important witness, Julio Jorge

Lopez (73), was disappeared and has never been heard of since. There is

evidence that former police were involved. This incident highlights the

risks facing witnesses and many other cases of harassment have been

reported, although a witness protection program is now in place.

2007:

La Plata: Miguel Etchcolatz , former head of the secret police in

the Province of Buenos Aires was condemned for 5 cases of homicide and

torture. It was during his trial that an important witness, Julio Jorge

Lopez (73), was disappeared and has never been heard of since. There is

evidence that former police were involved. This incident highlights the

risks facing witnesses and many other cases of harassment have been

reported, although a witness protection program is now in place.

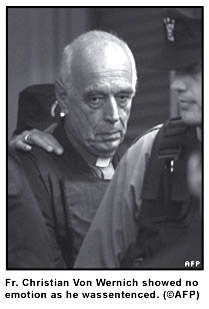

2008: La Plata: Roman Catholic priest Fr.

Christian Von Wernich, police chaplain during the dictatorship, was

condemned for his role in the disappearance and assassination of a group

of young people during the dictatorship. Despite the scandal involved,

the Church has not sanctioned the priest who continues to minister to

his fellow prisoners in Marcos Paz prison.

2008: Buenos Aires: The Fatima Massacre. That was

the mass killing of thirty prisoners mostly trade union activists taken

from a secret detention center in August 1976 and assassinated in

Fatima, a small rural community near Buenos Aires. One of the defendants

was acquitted on a medical alibi, the others were condemned.

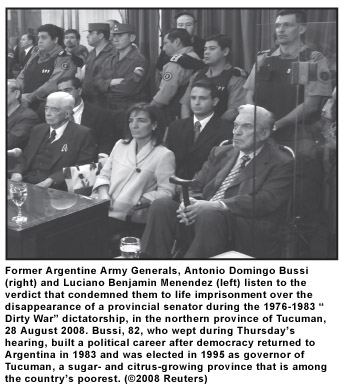

2008: Tucuman: Former generals Domingo Bussi and

Benjamin Menendez were condemned to life imprisonment for their role in

the disappearance of senator Vargas Aignasse in 1976.

2009: Buenos Aires Province: Gral Olivera

Rovere and other ranking officers were condemned for different cases but

other defendants were given light sentences or acquitted. There had been

many cases in other provinces and cities around Argentina including two

cases where military officers, who had adopted children of the

disappeared, were indicted and condemned for the crime of suppressing

the identity of those children.

Conclusion

Now many cases have completed the Instruction stage

and are at the trial process. One can say then that a characteristic of

the human rights trials in Argentina is that many are taking place in

different parts of the country and each one has its own characteristic.

The trials are certainly historic as it is the first time that families

and survivors have the opportunity of seeing perpetrators close up as

they are escorted handcuffed into the courtroom. That is a major

achievement. However, all seem unrepentant as they listen to the stories

of their cruelties and one is left is with many unanswered questions as

to their motivations and mentality.

We also hear the stories from witnesses and relatives

who go through the sufferings endured almost thirty years ago. The fact

that most are now older folk with their grandchildren listening to their

testimonies in the public gallery gives a special poignancy to the whole

situation. It is not easy to relive those situations but it is

significant that witnesses seem to remember every detail of their

traumatic experiences. Psychological assistance is offered and survivors

have organized support groups.

At the end of the day, however, all seem to be

worthwhile. There is a profound sense of achievement for witnesses and

families with a definite sense of closure. Impunity has not had the last

word. One has been able to tell one’s story in a courtroom and in front

of the perpetrators. The justice which is later handed down may be meek,

indeed considering the crimes involved but it is justice and there is a

definite sense that Never Again has become possible even with

that justice. The Argentine population is certainly privileged to be

able to finally break with impunity and live through this judicial

process. Hopefully, other countries will soon follow. That is what the

struggle of the families of the disappeared is all about: Truth,

Justice, Redress, Memory and Solidarity.

Patricio Rice was the Executive

Secretary of FEDEFAM from 1981 -1987. He is also a witness in some of

the human rights trials in Argentina.